Empowering women and oppressed genders through photography

The work of See It From Her+

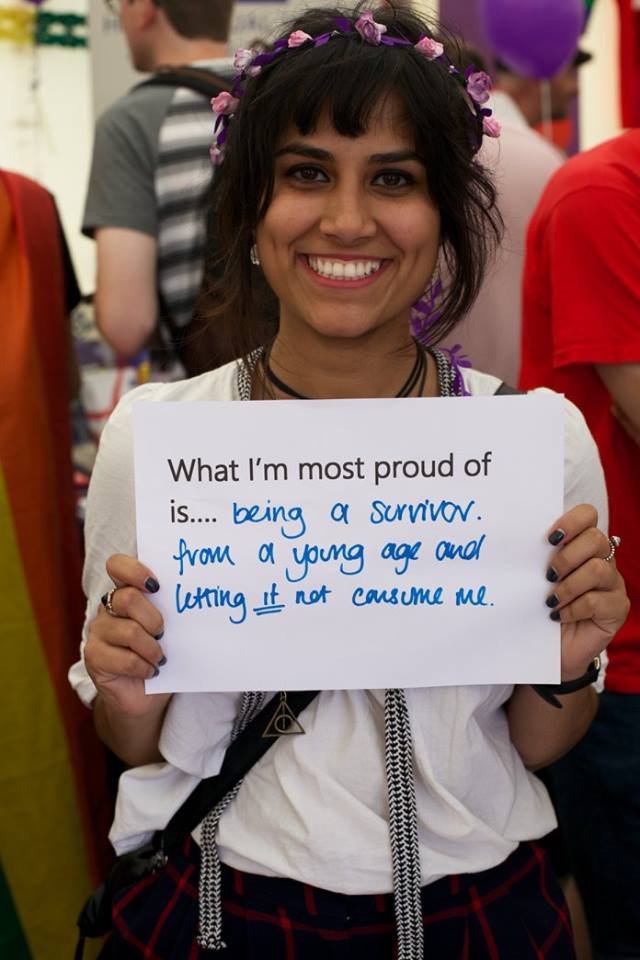

Through photography and image, See It From Her+ gives a platform for underrepresented voices to be raised and heard.

By Rute Costa

Bryony is the founder of See It From Her+, a project that supports women and those who feel oppressed because of their gender identity. Through photography and image, See It From Her+ gives a platform for underrepresented voices to be raised and heard.

I ask Bryony why she felt compelled to found her organisation: “It was a response to lots of things”, she explains, “not just a lack of representation of women and oppressed genders in the media, but also a lack of really accessible and safe spaces”. Throughout history, patriarchal structures have continuously misrepresented, undermined and silenced women, non-binary people and minority genders. Because of this, Bryony explains, “I wanted to create something that was completely fresh, a new structure led by people who experience multiple oppressions where we can all reshape our own identities”.

Within SIFH+ “there is no ‘us’ and ‘them’”, no hierarchy between those who are supporting and those who are being supported. Bryony clarifies: “structurally, we’re not supporting people in the ‘more usual sense’; we work with people who we share experiences or identities with, and we learn from each other”. To put it simply, they want women and people of oppressed genders to be able to tell their own stories: “we want our projects to be led by people who’ve experienced that issue, or that identity”. Bryony gives me the example of one of their first projects, for survivors of rape and sexual violence: “I was part of that project as a facilitator but also made work myself. So, it wasn’t like I was doing a project for survivors, I was doing a project with survivors as I am a survivor myself.”

“We work with people who we share experiences or identities with, and we learn from each other.”

I ask Bryony whether she knew, from the start, that photography would be the organisation’s main creative outlet: “it was always there at the beginning”. She explains that photography and images in the media have, for centuries, “misrepresented women and oppressed genders, and created false ideas of our stories”, and that SIFH+ are “using the same tools to challenge what we don’t feel is an accurate interpretation”. The words of photographer Berenice Abbott quoted on the organisation’s website suddenly ring a lot more true: “Photography helps people to see”. In this case, it helps people to see the real stories of women and oppressed genders, clearly and without distortion.

In their workshops and programs, SIFH+ give each participant access to a camera to use freely. “Why do you think a camera is such a fantastic tool for self-expression?”, I ask Bryony. She explains that a camera “is very accessible, especially because we work alongside lots of people whose first language is not English, or people who have complex mental health problems”. Not being forced to communicate verbally in the workshops means people feel less anxious and more at ease to share their stories. Also, Bryony explains, “with a camera, you can create something that looks good and powerful that you can feel proud of, very quickly.” Unlike drawing or painting, photography does not require years of trained skill to be judged as “good” or “accurate”. She expands: “you don’t have to worry about the making of the work, you just worry about what you want to say and how you want to say it. The tool is already there”.

Whereas now SIFH+ have cameras, at the very start the organisers lent their own equipment. I ask Bryony how it all began. Their first project was in collaboration with the Big Issue Foundation: a workshop with women who were homeless. “It was really exciting”, she recalls, “we went in with a basic idea of what we were going to do, and then the women led [the workshop] when we got there – we saw how powerful it was just to let people use cameras to show themselves, to share their stories”. Their model worked from the start. Shortly after, the end result from a workshop with survivors of rape and sexual violence was shown at a film festival, and projected onto a big screen in the square in the centre of Bristol.

“We wait for people to say ‘we need this’, and we go ‘right, now let’s try to find the resources to be able to do it’.”

Bryony tells me the workshops are not “about learning technical skills or how to be a good photographer, [they are] about supporting people to use [a camera] to explore their identity, a story or something that they want to say”. Even so, their ongoing Bourke-White programme – a ten-week mentoring program with female and gender non-conforming photographers – is open to all women and non-binary people in Bristol, and allows for some technical learning. Mentees refer themselves to request a mentor, and are free to choose what they want to take away from the project: they may want to learn photography skills, or embark on a more specific project about their identity and experiences. A current mentee plans to make a film about her life, and SIFH+ are supporting throughout this process.

Their upcoming projects sound as necessary and valuable as the previous ones. The organisation is planning a series of workshops with trans folk about trans misrepresentation which will lead up to a final exhibition and event. Alongside this, they will be conducting workshops with women and non-binary people who are or have been in detention centres. These projects will be led by those with lived experience. It sounds novel and exciting. “That’s very much what we like to do”, says Bryony, “respond to what people need […] we wait for people to say ‘we need this’, and we go ‘right, now let’s try to find the resources to be able to do it ’”.

The impact SIFH+ can have on the women and non-binary people who take part is evident. The most revealing moment, I get told, comes at the end of the workshops, when the work produced is shared with everyone on the projector: “people always get really excited about seeing their work, talking about it”. Bryony recounts two special instances, when, in just a couple of hours, they witnessed a clear shift in confidence. SIFH+ did a couple of workshops with women who had been trafficked, and women who had mental health problems. “In both those workshops when people arrived at the beginning they were all very anxious, didn’t want to look at each other or make eye contact”, she recalls. However, “throughout the workshop people started communicating more when they were making work, and, by the end, they were complimenting each other, having animated discussions about each other’s work, and actually left walking in a different way, holding themselves differently. I know from personal experience how much photography can help anxiety so it is exciting to see this with others too”.

“I know from personal experience how much photography can help anxiety so it is exciting to see this with others too.”

With every exhibition that SIFH+ do, they want an event to go alongside it. Bryony explains why: “whilst photography is an amazing tool, it’s the very start of the conversation”. The issues raised by the images lay the foundation for more in-depth discussion. SIFH+ organise big events that create the right atmosphere for these conversations to be had. Bryony cites their event Borderless, which happened last June, as one of her proudest achievements. They filled a day with photography exhibitions, short films, food, drink, various workshops (including a Voguing lesson), and two panel discussions: one on understanding sexism, objectification and rape culture, and another on xenophobia, racism and hate crime. All of their invited speakers are experts by experience – instead of inviting academics who study these issues, they give a platform to people who have gone through them. To wrap up the day, they welcomed performances from female and non-binary artists. Bryony is happy to have been part of bringingt “lots of different people together into the same space”.

SIFH+ try to be as resourceful as they can: in the first seven months of their existence they managed to run five projects with a £130 budget, and they join forces with other organisations to share spaces and resources. However, financially, they are still falling short of their needs. Bryony tells me that events like Borderless, as well as equipment, cost a considerable amount. The grants they apply for impose certain restrictions that are incompatible with the way SIFH+ work: time-limited, demanding specific outcomes, and detailed evaluations, grants don’t give them permission to grow and change the direction of their projects. A better source of funding is needed to allow them to move forward with their work.

“And what does the future hold?”, I ask. The organisation’s priority is to source enough funding to provide users with what they need to pursue their individual projects. In five years they hope to be “a resource space where people can come and get advice, support and the resources to create their own projects”. SIFH+ want to establish links and collaborations with spaces in London and Bristol, so they can quickly organise exhibitions. Bryony finishes by capturing the ideal picture, one not far from possibility:. “We want to have premises – a space where people can run workshops, a space that is very accessible and safe, where people can come to have discussions and make work. A space that is owned by all of us”.

Photo credits: See It From Her+