Herstory: Championing the women history hid away

Alice Wroe’s project uses feminist art to to engage people of all genders with the women’s history that has been systematically left out.

By Rute Costa

“I was listening to the radio about four years ago, and it was women’s hour, and there was this song over the top that is from Mary Poppins. It goes: ‘Our daughters’ daughters will adore us/ And they’ll sign in grateful chorus/ “Well done! Well done!/ Well done Sister Suffragette!’ I was kind of half listening, half not listening, and then it really hit me in my stomach that I’d never felt like saying ‘well done’ or ‘thank you’ to any woman who’d come before me.”

This is Alice. She is telling me about Herstory, her project using feminist art to engage people of all genders with the women’s history that has been systematically left out. Alice is recounting what sparked the idea: the moment she realised she hadn’t “just landed here”, and that she couldn’t live her life “in isolation” from the historical women who paved the way to her present moment. She continues: “I felt really surprised, and I started researching […]. If I went to a particular event, or I was walking in a particular area, I would start looking up these women, and they were everywhere. It had such a profound impact on me: I felt bigger, and fuller, and taller, I felt like I took up more space in the world.” But then, the harsher side to this reality hit her: “I started to feel massively angry, and hurt, and let down by my education. That it had taken me to be in my early twenties, on my own, by chance listening to the radio, until I had this feeling of fullness, and coming from something.”

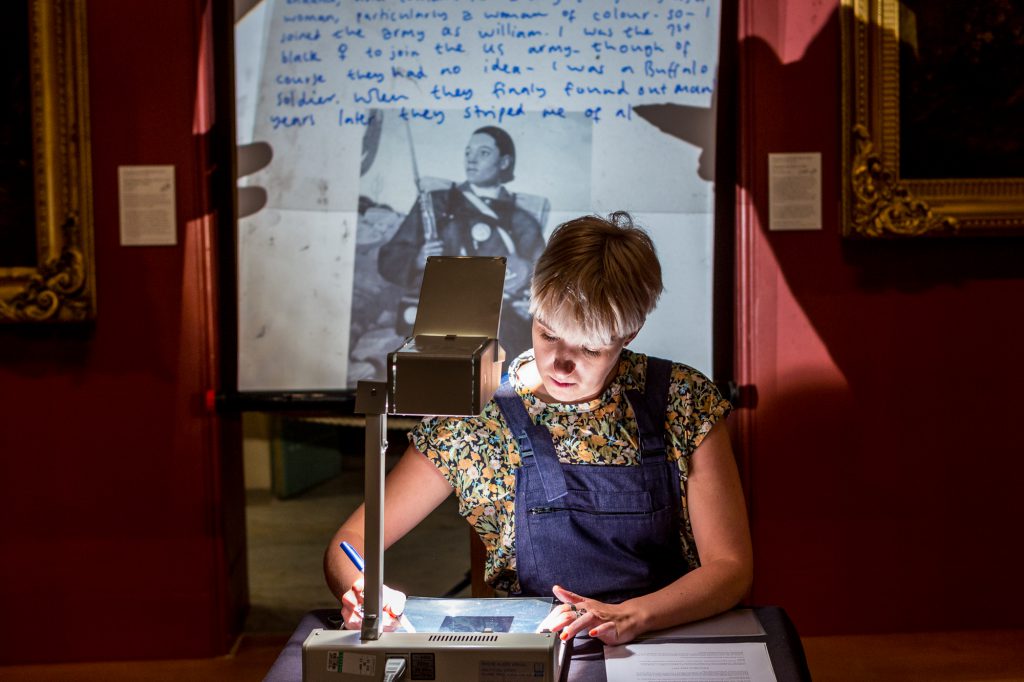

It wasn’t enough to wait for other women to, by chance, reach the same realisation. So, Alice decided to do something about it. She began running workshops at schools to ensure more students were exposed to women’s history, and soon she settled on a working format: “I recreate The Dinner Party, an artwork by Judy Chicago which is in the Brooklyn Museum in New York. It’s a really large table in a triangular shape, and each place setting is a different woman from history represented”. However, she didn’t feel that merely recreating it was enough either. “[The artwork] was static and fixed. I felt it could be really exciting if we, as a group of people, populated it”. And so, in Herstory workshops, each participant will arrive to find a folder of compiled research about an unknown woman in history previously put together by Alice herself. They are then invited to absorb it and go through the process of “imbuing their own lives into that narrative”: selecting the information that is relevant to them and presenting it to the rest of the party in the first person, as that woman.

“It had such a profound impact on me: I felt bigger, and fuller, and taller, I felt like I took up more space in the world.”

Alice tells me that this particular method of encouraging the participant to embody the stories, and ‘write’ their own herstory out of them, comes from another life changing realisation: “that [history is] basically one person seeing something, having the privilege, the education and the social standing to be taken seriously, writing it down, and it just slips into our history books and it becomes fact”. Herstory is inviting participants to question the sources of the history we have been taught, the privileged (often white male) voices behind it, and how they have systematically been silencing women’s stories. The project is propelling participants to reclaim those stories: “it’s about disrupting that hierarchy of whose history is shared, who does that sharing, and whose life is imbued into it”.

In Herstory workshops, Alice explains, “there are never any silent witnesses, everyone has to participate”. I ask whether people ever feel uncomfortable borrowing the voices and inserting themselves into the stories of these women. “People do get nervous, and you hear the voices quiver, and I just love them even more for it because it’s so brave”, she tells me. “The space is really vulnerable”, and, therefore, Alice explains, “we have to support each other: we are championing the women but we are championing each other first and foremost”. The result is a collaborative “performance artwork”, accompanied by everyone’s “woops and cheers”. In Alice’s words: “It’s a really lovely moment”.

Every workshop is different because it introduces a distinct group of woman’s stories. Alice’s research, aided by the recommendations she is gifted by participants, continuously help her find a plethora of ‘new’ historical women. Curious, I ask about some memorable figures that have featured on Herstory so far. She tells me of Lily Parr, the footballer extraordinaire with a killer left kick. Whilst playing for Dick, Kerr’s Ladies F.C., one of the earliest known women’s association football clubs in England, Parr proved time and time again that her strength as an athlete put her on an equal level to her male counterparts. Alice tells me she once broke a goal-keeper’s arm during a penalty after he openly and misogynistically doubted her skills.

Like Lily Parr, many other women herstorically have lifted themselves out of the stereotypes of womanhood or femininity in which society encaged them. “Irena Sendler is one that I talk about a lot”, Alice says. Sendler was a Polish nurse and social worker who, during the Second World War, was responsible for smuggling thousands of Jewish babies and infants out of ghettos. As the driving force of Zegota, the underground Council to Aid Jews, Irena saved about 2,500 children from the Holocaust, and reinserted them with Polish families. “She was risking her own life every day to save these children […] That is sheer bravery. You tell people: boys are brave, girls aren’t brave and there she was!”

“Herstory is inviting participants to question the sources of the history we have been taught, the privileged (often white male) voices behind it, and how they have systematically been silencing women’s stories.”

Similarly, the Match girls “rupture[d] what we think of as womanly or not womanly”. They were a group of young female workers from the Bryant and May match factory who went on strike in 1888. Subject to fourteen-hour working days, poor pay, astronomic fines, and illnesses like phossy jaw, these young women and their fight for workers’ rights made it to the newspapers and to parliament. The impact was profound: “It sparked workers to organise themselves across the country, and that was a group of young girls – you wouldn’t think that when you think of the Labour movement in this country”, says Alice.

The list of remarkable women is endless. Alice also tells me about Annie Edson Taylor, an American retired teacher and a widow who, having no financial income for her retirement, decided she would be “the first person to go down Niagara Falls in a barrel”, and earn money by speaking about her experience. Brave and ingenious, Taylor sent her cat first to test the waters, and then safely threw herself off the cliff. On much more stable ground, Moms Mabley stepped onto stages as one of the first female American stand-up comedians: “she was talking about race, about gender, about sexuality at a time when no one was talking about those things – let alone a woman, let alone a gay woman of colour”. As Alice recounts these stories, I am surprised and disappointed I haven’t heard them before. It’s a common feeling.

Alice’s work aims to fill in the absence of women’s stories in schools, history books, and people’s lives. Her first audiences were students, and that remains a crucial part of the project: at the start, she “would always be asked by a brilliant feminist teacher” who was trying to make the curriculum more inclusive, but now more and more groups of young feminist organisations invite Alice directly. “That shows that the relationships that schools have to what I’m doing has shifted hugely, and is led by the young people now”, she says. This does not mean that Herstory is just a project for “girls”. On the contrary, Alice is adamant “we have got to poke holes in the canon generally, make spaces big enough, clamber in, and populate it with the fantastic women who have lived and worked. If we only show that to the girls, then it will carry on like it has been.” Structural change is necessary.

“We have got to poke holes in the canon generally, make spaces big enough, clamber in, and populate it with the fantastic women who have lived and worked.”

Herstory is for all people, regardless of gender and age. Soon after starting in schools, Alice received interest from adults who, to her surprise, wanted to do it too. But how is Herstory different as an experience for each of these audiences? She explains: “With a group of students, it’s special because they are young and […] you see them building up who they want to be, and the idea that these women’s stories will embed themselves into their growth is exciting”. Alice also speaks of how important it is to “give [students] positive role models of other genders, and have young men take on the character of a woman in the first person and it being an empowering act”, as opposed to something funny or diminishing (as it is usually seen as).

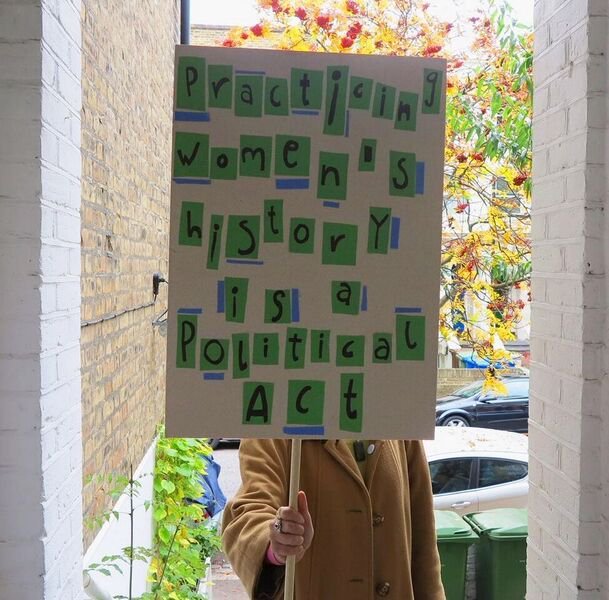

With adults, Alice confesses, “we all feel really sad at the beginning [of the workshops]”. There is a collective moment in which “you realise all of the musicians and artists that you’ve learnt about, all of the writers that you’ve studied are male: women’s history comes as this ad on at the end”. Alice tells me this realisation adds extra weight to the already important workshops: “there’s a real sense of political urgency that we have to share [women’s stories] with each other because if we don’t this is will go on and on”. The founder believes wholeheartedly that “sharing women’s history is a political act, and as we do it as this performative artwork, together, we are disrupting the canon that’s just engulfed us all”.

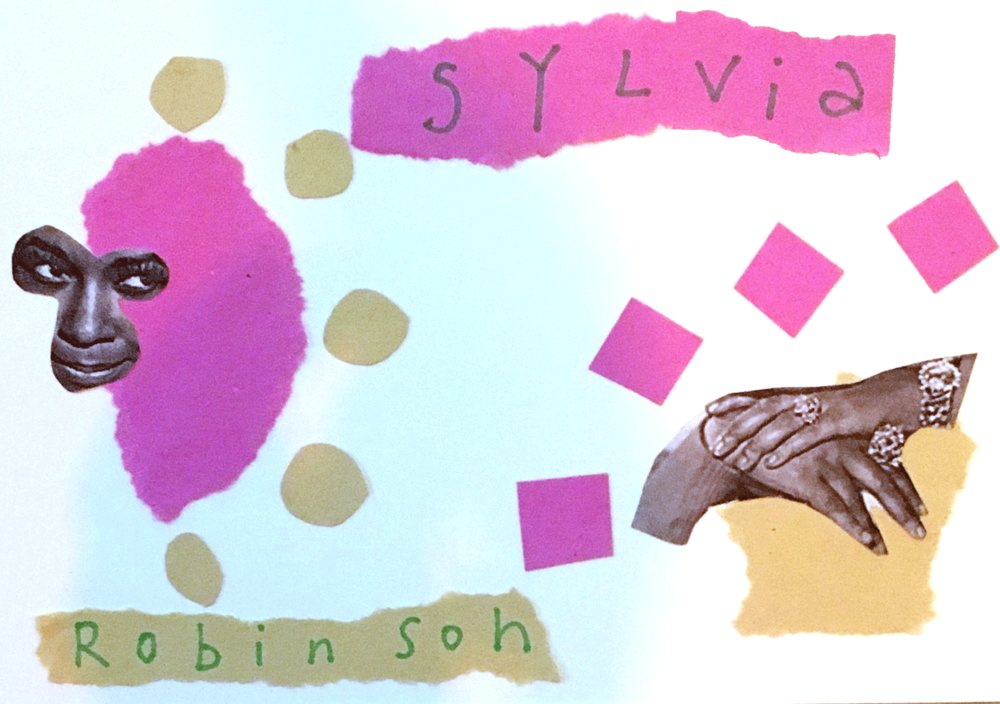

Another way in which the project engages with feminist action is through collage. At the start of the workshops, Alice gifts each participant with a collage of the woman they are about to represent. The first time they encounter her is in collage form, cut up, beautifully in pieces. Only later, once they have done the research and got a sense of who the person is, do they get to see a unified image. Alice believes that “in a world where we’re treading this really narrow line of what is beautiful […] to liberate the woman’s body, to burst it apart, to cut it up, is a radical feminist act”.

“Collage is wonderful because there is a really strong history of feminist collage-making”, she adds. Dada artists like Hannah Höch were “cutting and sticking the notion of the new woman: […] looking more androgynous, going out to work, blurring the boundaries between what was expected of a woman and what was expected of a man”. In the 90s, zine culture linked up young women across America and the UK to talk about feminism, music, their lives. But before this, a group of ingenious women had already taken action through collage. In the beginning of the twentieth century, the Suffragettes, were “scrapbooking […] cutting, sticking, and pasting their own stories, when no one was sharing [them]”. They collected, cut and pasted written accounts of the daily marches, badges and critical newspaper articles whose photos of the ‘enemy’ they (hilariously) defaced.

“We have to learn from the really quite painful difficult things that are also true of the history of feminism. If we airbrush out the racism, the homophobia that was inherent in so much of history, then we don’t stand to gain anything.”

This gives me a chance to ask Alice about the suffrage centenary this year, a part of women’s history that is getting well-deserved attention. “Because women’s history has so often been left out”, she explains, “there’s a risk of jumping onto it, brandishing it out”. Alice is well-aware that only “a very small percentage of women” could vote in 1918, leaving out many groups of women who were denied that right. Her view is that we must not forget them: “we have to learn from the really quite painful difficult things that are also true of the history of feminism. If we […] airbrush out the racism, the homophobia that was inherent in so much of history, then we don’t stand to gain anything”.

Alice believes in looking back in order to move forward. “We have to recognise how it would have felt to be left out that polling station. And then we need to look at our own feminism [now] and think about who is vital to this movement, who is at the campaigns, writing the text, being at the very edge in terms of risk and fear – who are those voices and when do they not get a platform?” She mentions the example of trans women, who are often at the very front of the movement, and also “at the very end, getting the sharpest end of patriarchy”, who are very much part of a feminism that often excludes them. Alice puts it simply: “it’s just looking back and learning the lessons of the past to create the movements of the future”.

In her future, Alice intends to keep running the workshops, sharing the stories and being told about new women to research. But she is also “working out creative ways to activate the research, to kind of burst it beyond the realms of the project”. Last year, Alice worked with U2 and their team to curate a piece entitled HERSTORY for their world tour, which “showcased different women from history behind the band as they played [Ultraviolet]”. She is now looking for even newer ways to fill the gaps of women’s history at events and organisations: “So when there are big moments, big days in our history, I want women to be at the front and to be sharing those stories”. A good example would be the suffrage centenary. On that day, Alice would have wanted to celebrate women like Sophia Duleep Singh, an Indian suffragette and it-girl who used her fame to attract attention for the cause and move it forward, and Edith Margaret Garrud, a jiu jitsu expert who taught the suffragettes to defend themselves and their peers from violent police.

Herstory is not just telling stories: it’s taking action, calling for a much-needed disruption of female misrepresentations in the past, and carving out the space for the forgotten yet remarkable women in history. Alice is starting and nurturing a crucial conversation about women’s stories, hoping it will branch out, be shared, and become the norm in our present and future. It’s about time we put ‘Her’ back in History.

Photo credit: Herstory